Frostfestigkeit einer Schale

Eine Bonsaischale wird meist als eine Einheit angesehen, besteht bei glasierten Schalen jedoch aus zwei unterschiedlichen Dingen, einmal dem Scherben, damit meint der Fachmann aber nicht eine zerbrochene Schale, sondern man versteht darunter den Schalenkörper, den aus Ton geformten Gegenstand und der Glasur. Die Glasur, ob glänzend oder matt, ist der Überzug oder das Kleid der Schale.

Beide Scherben (Schalenkörper) und Glasur müssen in ihrem Ausdehnungsverhalten genau aufeinander abgestimmt sein, sonst entstehen Glasurrisse, Abrollen der Glasur, Kantenabsprengungen und ähnliche Glasurfehler.

Zum Schalenkörper, dem Ton.

Alle Tonarten sind unterschiedlich, denn Ton ist ein Naturprodukt. Man findet kaum eine Tongrube, die einer anderen in der Tonqualität gleich ist. Der Töpfer muss also genau bestimmen welche Tonsorte er für seine Schalen verwendet und bei welchen Temperaturen er die Schale brennt, damit sie frostfest wird. Die Frostfestigkeit einer Schale wird nach dem Wasseraufnahmevermögen des Scherbens berechnet.

Frost-resistance of a Pot

A bonsai pot is usually regarded as one unit, but glazed pots are composed of two different materials, which are the clay body of the pot and the glaze. The glaze, glossy or matt, ist the coating or the dress of a pot. Both the body and the glaze must match in their dilation characteristics, otherwise glaze fissures, glaze drips, blasted edges and similar glaze flaws can occur.

Let us regard the pot's body, the clay.

All sorts of clay are different because clay is a product of nature. You will hardly find two clay pits with the same clay quality. The potter must exactly determine which sort of clay he uses for his pots and at which temperatures he fires them to make them frost-resistant. The frost-resistance is calculated from the water absorptive capacity of the clay body.

Frostschaden an einer hochwertigen asiatischen Schale

Frost damage on a high quality Japanese pot.

Schaden im Inneren der Schale / Damage inside the pot.

An Dieser Schale sind beide Frostschäden zu sehen.

(Fotos: Dale Cochoy, Ohio USA)

1. Die Chips, die sich abgelöst haben, kommen von dem Wasser, das in den Schalenkörper eingedrungen ist, und der Frost hat sie abgelöst.

1) The chips that have come off were caused by water soaked into the clay body of the pot.Then frost has blasted the chips out.

2. Der Riss an der Ecke der Schale kommt von dem Druck, den die gefrorene Erde auf die Schale ausgeübt hat.

2) The crack in the corner of the pot was caused by the pressure of frozen soil against the pot's walls.

Der Test.

Nehme eine kleine Tonplatte und wiege sie nach dem Hochbrand oder gleich die fertig gebrannte Schale. Dann koche diese ca. fünf Minuten auf. Damit kleine mit luftbesetzte Hohlräume verschwinden, und diese sich mit Wasser auffüllen können. Danach wiege die Tonplatte oder Schale noch einmal ab. Die Gewichtszunahme darf jetzt nicht über 2 % liegen, dann ist die Schale frostfest. (PS. hierauf muss ein Töpfer Garantien geben)

Die Dichtbrandtemperatur ist diejenige, bei der die Wasseraufnahme des gebrannten Tones unter 2 % liegt.

The Test

Take a small clay slab and weigh it after high-firing or take a ready fired pot. Then cook it for about five minutes, so that small air-filled cavities can fill with water. Then weigh the slab or

pot again. The weight may not increase more than 2% if the pot is to be frost-resistant. (By the way, a potter must guarantee this!)

The tight-firing temperature is that at which the clay gets a water absorptive capacity of less than 2%.

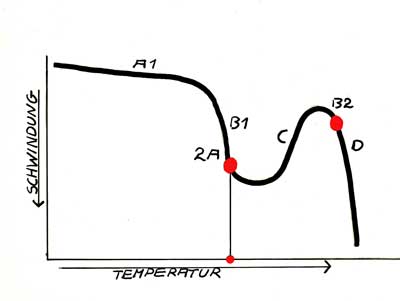

Brennkurve

Die Brennkurve eines Tones am Anfang ohne große Schwindung (Linie 1). Ungefähr bei ca. 1000° C setzt eine Schwindung des Tones ein (Linie B1) bis zu einem bestimmten Punkt, von dem an sich der Ton aufbläht, z.B. Blasen wirft, (Linie C) ab dann schmilzt der Ton in sich zusammen. (Linie D)

Die Dichtbrennkurve liegt vor dem Kurvenknick (Punkt 2A). Der Kurvenknick entspricht der größten Schwindung. Der Kegelfallpunkt (B2 nur für Töpfer) hinter dem Kurvenblick entspricht der größten Aufblähung.

Mancher Ton brennt bereits bei 1200° C schon fast dicht, hält aber eine Brenntemperatur bis 1700° C aus. Es ist aber für Bonsaischalen unsinnig, so hoch zu brennen, nur um eine Wasseraufnahme von 0,0% zu erreichen, es wäre auch viel zu riskant.

Bei bis zu 2% Gewichtszunahme spricht man von gesinterter Ware, von 2 - 5% von halbgesinterter Ware (nicht frostfest), von über 5% Gewichtszunahme von poröser Ware (absolut nicht frostfest).

Frostfestigkeit hat also etwas mit der Porosität einer Schale zu tun.

Porosität einer Schale und der Erde in ihr.

Ein wesentlicher Faktor für die Frostfertigkeit einer Schale ist auch die Erde. Normalerweise ist die Erde, hier besonders Akadama-Erde, porös genug um die Ausdehnung des Eises im Inneren der Schale aufzufangen. Zudem trägt ein entsprechend großes Abzugsloch bei, dass die Schale nicht voll Wasser läuft. Es bleiben also noch genug Porenräume offen, in denen sich das Eis ausdehnen kann, ohne die Schale zu sprengen. (PS. einen solchen Frostschaden muss der Schalenbesitzer tragen).

Die Beschaffenheit einer Schale gegenüber Frost (wie oben beschrieben) hat also auch etwas mit Porosität zu tun. Der Schalenkörper darf sich nicht mit Wasser füllen. Der Töpfer muss durch höheren Brand dafür sorgen, das die Sättigungsfähigkeit herabgesetzt wird. Die Schale muss mehr geschlossene und nicht durchströmbare Poren aufweisen.

Zum Schalenkleid, der Glasur.

Auf keinen Fall darf man porös gebrannte Schalen glasieren, weil hierdurch die Oberflächenporen verstopfen würden. Eiskristalle könnten sonst nicht aus den Poren heraustreten und damit die Glasur in Schollen von der Schale abheben. Eine Glasur alleine macht eine Schale nicht wetterbeständig. Eine dicht gebrannte Schale hingegen nimmt kein Wasser auf, das Eis kann somit die Schale nicht gefährden, dadurch ist sie frostfest. Die Schale und auch die Glasur sind ein Werk des Feuers. Ein Schalentöpfer muss sich mit der Kraft des Feuers auseinandersetzen, denn hier zeigen sich die meisten Fehler wie Brand-oder Glasurrisse. Glasurrisse, feine bis grobe, entstehen oft unmittelbar nach oder auch noch nach geraumer Zeit nach dem Brand. Diese Risse entstehen hauptsächlich durch Zugspannung der Glasur. Die Spannung entsteht durch Ausdehnungsunterschiede von Glasur und Schale. Durch diesen Glasurfehler besteht also für die Schale Frostgefahr.

Achtung!!! Auch Craquelè Glasuren (im alten China „gesprungene Glasur“) sind eigentlich Glasurfehler, nur hierbei wird der Fehler absichtlich herbeigeführt. Nach dem Hochbrand bilden sich kleine feine Spannungsrisse spinnnetzartig über der Schale aus. Danach werden die Risse noch eingefärbt, um sie besser sichtbar zu machen. Auch diese Schalen sind nicht frostfest!! Auch bei zwei unterschiedlichen Bränden z.B. Schale hoch brennen und dann eine niedrig brennende Glasur aufbringen und nochmals brennen, machen eine Schale noch lange nicht frostfest.

Noch ein kleiner Frosttest.

Man hängt die Schale am Daumen oder Zeigefinger auf, (diesen kleinen Test kann man auch vor Ort bei dem Händler oder Töpfer machen). Je höher jetzt der Klang beim Anschlagen mit dem Knöchel der anderen Hand, umso frostfester ist die Schale. Der Klang muss rein sein und lange nachschwingen. Ist eine Schale nicht frostfest, gibt es einen dumpfen Klang und er schwingt nicht nach. Ganz geübte Schalenfreaks können die Frostfestigkeit auch mit der Zunge spüren. Nicht frostfest ist ungefähr so als würde man mit der Zunge ein Löschblatt berühren. Frostfest ist, als würde man eine Glasscheibe berühren. Und zu guter letzt der „Spucke Test“, und der geht so: etwas Spucke auf die Fingerkuppe und damit die Schale benetzen, (bei glasierten Schalen innen testen). Zieht die Feuchtigkeit schnell ein, ist die Schale nicht frostfest, bleibt die Feuchtigkeit lange stehen, ist sie frostfest.

The firing curve of a clay shows little contraction at the beginning (line 1). Approximately at 1000°C a contraction of the clay starts

(line B1) up to a certain point at which the clay inflates and blisters for example (line C). From then on the clay melts together (line D).

The tight-firing curve lies before the bend of the curve (point A2). The bend marks the greatest contraction. The pyrometric cone equivalent (B2, for potters only) after the curve bend marks the

greatest inflation.

Some clay almost tight-fires at 1200°C already but can endure a firing temperature up to 1700°C. It makes no sense however to fire bonsai pots this high just to reach a water absorptive capacity

of 0.0% and it would be too risky too.

Up to 2% weight gain we speak of sintered ware, at 2 - 5% of semi-sintered (not frost-restistant), at more than 5% weight gain it is porose ware (absolutely not frost-resistant). So

frost-resistance is linked with the porosity of a pot.

Porosity of a pot and the soil inside it

An important factor for the frost-resistance of a pot is also the soil. Normally the soil, especially Akadama-substrate, is porose enough to compensate the expansion of the ice inside the pot. A

big drainage hole also helps to prevent the pot from filling up with water. There remain enough open pores in which the ice can expand without blasting the pot. (By the way, such damage must be

covered by the owner of the pot).

The characteristics of the pot concerning frost (as described above) are connected to its porosity. The pot's body must not soak up water. By means of higher firing, the potter reduces the

saturation ability. The pot must posess more closed and impermeable pores.

The pot's dress, the glaze

Porose fired pots must never be glazed because this would clog up the surface pores. Ice crystals then would be unable to emerge from the pores and would lift the glaze in chunks off the pot. A

glaze alone does not make a pot frost-resistant. A tight-fired pot however does not soak up water, the ice can not endanger the pot so that it is frost-resistant. The pot and the glaze are a

product of the fire. A bonsai potter must deal with the power of fire, because here most of the damages like firing fissures or glaze fissures occur. Glaze fissures, delicate to coarse ones,

occur directly or some time after the firing process. These fissures are caused mainly by tensile stress of the glaze. Dilation differences between glaze and pot are responsible for this. This

glaze flaw means a reduced frost-resistance!

Beware: Even craquelé glazes (in old China “cracked glaze”) are actually glaze flaws, only this flaw is produced intentionally. After high-firing delicate little tension fissures spread like

cobwebs over the pot. Afterwards they are dyed dark to make them more visible. These pots also are not frost-resistant!

Two different firing processes, for example high-firing a pot, then applying a low-firing glaze and firing again, do not make a pot frost-resistant.

Another little frost-resistance test.

Hold the pot with thumb and forefinger (you can do this at your trader's or potter's place). The higher the sound when you strike the pot with the knuckles of the other hand, the more

frost-resistant is the pot. The sound must be pure and long-lasting. If a pot is not frost-resistant, it has a dull sound and it does not last. Very experienced pot enthusiasts can even sense the

frost-resistance of a pot with their tongue. Not frost-resistant pots feel as if you touched a blotting paper with the tongue. Frost-resistant pots feel like licking at a glass pane.

The “spittle test” works like this: put a small amount of spittle on your fingertip and then dampen the pot with it (on the inside of glazed pots). If the moisture is quickly absorbed, the pot is

not frost-resistant; if the moisture stays long on the surface, it is frost-resistant.

Der "Härtetest" / The “Endurance Test”

Peter Krebs

Alle Fotos und Zeichnung Peter Krebs

All photographs and drawing by Peter Krebs

Translation: Heike van Gunst