Kleine Schatztruhe Nr. 1 / A Little Treasure Chest 1

Aus China kam es, mit Gold wurde es aufgewogen. Marco Polo nannte es „ Porzellana“.

Von der Kaurischnecke mit ihrem glatten, glänzenden Haus kommt der Name -Porcella-. Wir nennen es heute Porzellan. Die Beschäftigung mit Porzellan gleicht einem Abenteuer, einem Abenteuer zurück

zu den Anfängen der Kunst/Keramik herzustellen. Vor etwa 700 Jahren berichtete schon ein europäischer Kaufmann von der allerhöchsten Feinheit dieser Keramik, die an Glas erinnert, aber eine

weitaus höhere Festigkeit aufweist. Im Jahre 1271 unternahm Marco Polo mit seinem Vater und Onkel eine Handelsreise nach Peking. Nach seiner Heimkehr im Jahre 1292 brachte er neben anderen

Handelsgütern auch Porzellan mit und damit auch den Bazillus, dem man das Porzellanfieber zuschreiben könnte.

Dieses Porzellanfieber brach dann auch europaweit aus. Italienische Fayence- und Glasmacher, deutsche, französische und englische Keramiker suchten verzweifelt nach dem Stoff, um solch herrliche

Kostbarkeiten herzustellen. Den Stoff, bei dem Fürsten und Könige schwach wurden.

Die hier vorgestellten Porzellanschalen stammen alle aus China.

It came from China and was worth its weight in gold. Marco Polo coined the term 'porcellana' - derived from the word 'porcella' for the cowry with its smooth and shiny shell. Today we call it porcelain. Exploring the history of porcelain is an endeavor which takes us back to the beginnings of the art of producing ceramics. About 700 years ago, a European merchant gave an account of the high degree of fineness of this ceramic, which is reminiscent of glass, but much more durable. In 1271, Marco Polo made a trading voyage to Peking with his father and his uncle. On his return in 1292, among other goods, he brought back porcelain, and with it a bacillus that started the porcelain fever.

This fever broke out all over Europe. Italien fayence and glass makers, German, French and English potters desperately sought out the material to produce such splendid treasures. It was the stuff the sovereigns and kings desired.

The porcelain pots shown here are all from China.

Größe: Durchmesser 28 cm x 18 cm hoch Alter: ca. 80 – 100 Jahre

Size: Diameter 28 cm, height 18 cm. Age: 80 - 100 years

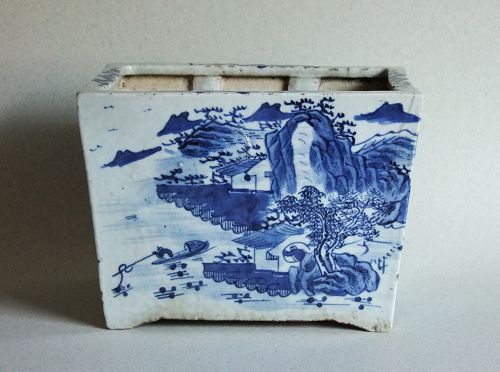

Größe: 19,5 cm x 19,5 cm x 15,8 Alter: ca. 80 – 100 Jahre

Size: 19,5 cm x 19,5 cm x 15,8. Age: 80 – 100 years

Größe: 22 cm x 15,7 cm x 16,3 cm Alter: ca. 80 – 100 Jahre

Size: 22 cm x 15,7 cm x 16,3 cm. Age: 80 – 100 years

Die Landschaftsmalerei auf dieser Schale wurde sehr dynamisch und spontan

aufgebracht, fast schon modern.

Auf der Innenseite der Schale, noch sehr gut zu sehen, Verstärkungsstreben. Sie sollen einem Verzug während des Brennvorganges entgegenwirken. Heute wird diese Technik so gut wie nicht mehr

verwendet.

The painting on this pot was applied in a dynamic and sponaneous manner, almost modernist. The inside of the pot shows reinforcements struts that were used to avoid warping during the firing process. Today this technique is hardly used any more.

___________________________________________________________________________

Die hier im „Kleinen Schatzkästchen“ vorgestellten Schalen stammen

alle aus der Sammlung von Paul Lesniewicz.

Text und Fotos: Peter Krebs

All pots shown there are all from the collection of Paul Lesniewicz.

Text and photographs: Peter Krebs

Translation: Heike van Gunst

In China, dem Ursprungsland der Jahrtausende alten Bonsaikunst, waren die ersten

Gefäße, in denen man die in den Bergen gesammelten Bäumchen pflanzte, Kult – oder Wassergefäße. Da diese Gefäße keine Wasserabzugslöcher hatten, wurden sie nachträglich in den Schalenboden

gebohrt.

Es ist nicht überliefert, wann die Töpfer in China ihre ersten Aufträge über die Herstellung einer Bonsaischale bekamen. Sehr alte chinesische Schalen zeugen heute davon, dass sich der Wandel vom

Kult – zum Bonsaigefäß nur langsam vollzog. Gefäß wie Bonsai waren beide noch religiöse Kultgegenstände.

Leider sind in den Wirren der Kulturrevolution unzählige dieser herrlichen Gefäße zerschlagen worden. Die wenigen heute noch existierenden alten Schalen werden ihrer Kostbarkeit wegen nicht mehr

als Pflanzschale benutzt, sondern als Zeugen der Vergangenheit in Museen oder Privatsammlungen aufbewahrt.

Um in den Genuss der Betrachtung und des Studiums alter Bonsaischalen zu kommen, müsste man schon nach Japan, China oder Taiwan fliegen. In Europa gibt es nur drei oder vier Orte, an denen alte

Schalen für jedermann frei zu betrachten stehen. Es sind dann auch meistens gleichzeitig die Privatsammlungen der Schalenliebhaber.

Im Bestand der öffentlichen Museen sind im Bereich „Asiatische Kunst“ so gut wie keine Bonsaischalen vorhanden. Eine Alternative zu dieser nicht gerade guten Situation ist diese Web-Seite oder

auch im Handel zu bekommende Bonsai Zeitschriften. Hier werden Bonsaischalen vorgestellt, die sonst für uns unerreichbar sind Das Wissen und Studium alter Schalen ist für den anspruchsvollen

Bonsailiebhaber unumgänglich. Erst hierdurch bekommt er Sicherheit im Umgang mit der Schale zu Bonsai.

Schalen zum Träumen

In China, which was the origin of bonsai art a few thousand years ago, ritual vessels and water containers were the first containers in which the small trees collected in the mountains were planted. Since these containers didn't have drainage holes, they were later drilled into the bottoms of the pots. We don't know when potters were consigned to build bonsai pots for the first time. Very old Chinese pots indicate that there was a gradual change from ritual vessel to bonsai pots. Both the bonsai and the pot were originally objects of religious cult. Unfortunately many exquisite pots were destroyed in the turmoil of the cultural revolution. The few pots that still exist are precious and therefore no longer in use as planting containers. As witnesses of the past they can only be found in museums or private collections.

You would have to travel to Japan, China or Taiwan in order to be able to enjoy viewing and studying such old bonsai pots. In Europe there are only three or four places where they are on display. In most cases, these are private collections; there are hardly any pots to be found in the "Asian Art" sections of public museums.

This web site wants to offer an alternative, as do some of the available bonsai journals. Here you can see pots that would otherwise be inaccessible. The knowledge and the study of antique pots is essential for the discriminating bonsai enthusiast, since it provides you with a deeper understanding of the relationship between pot and bonsai.

Pots To Dream Of

Größe: 18,5 cm x 18,5 cm x 14,5 cm Alter: ca. 80 – 100 Jahre

Size: 18,5 cm x 18,5 cm x 14,5 cm Age: 80 – 100 years

Größe: 16 cm x 16 cm x 18 cm Alter: ca. 80 – 100 Jahre

Size: 16 cm x 16 cm x 18 cm Age: 80 – 100 years

Ein beredendes Zeugnis aus alter Zeit ist diese Schale. Ich benenne sie einmal ganz

frei „Schale der vier Jahreszeiten“

Dargestellt wird hier die Königin der Blumen, die „Päonie“ (Chin. Mu-tan). Sie ist das Blumensymbol für den Frühling (erste Foto links). Poeten haben ihr gehuldigt, und ihre Schönheit steht für

höchste Erotik. Auf dieser Abbildung wird sie nicht im Zusammenspiel mit anderen Pflanzen gezeigt. Das bedeutet, dass sie hier nur für den Frühling steht. Mit anderen verschiedenen Pflanzen

gezeigt, könnten die Bedeutungen auch ganz anders sein.

Es folgt der Lotos (Zweite Foto links)

Der Lotos ist eine der acht buddhistischen Kostbarkeiten. Der Lotos steht für den Sommer, und unzählige Bedeutungen haben die einzelnen Konstellationen mit anderen Pflanzen.

Blüten, Knospen, und Samenstöcke sind voller Zeichen und Symbole, und durchweben den Lotos mit poetischer Erotik.

Die Chrysantheme (Chin. Chü, zweite Bild rechts) ist die Blume des Herbstes, sie steht für langes Leben. Auch hier wieder haben Konstellationen mit andern Natursymbolen unzählige

Bedeutungen.

Die Pflaume, (Chin. Mei, erste Foto rechts) oder der Pflaumenblütenzweig ist ein Pflanzensymbol für den Winter. Oft, so wie auch auf unserer Schale, wird er zusammen mit dem Bambus und der Kiefer

gezeigt, es sind die drei Freunde der kalten Jahreszeit.

Auch die Pflaumenblüte hat im Zusammenspiel mit anderen Symbolen überwiegend erotische Bedeutung.

Selbst die Schmetterlinge auf den einzelnen Bildspiegeln haben erotische Bedeutung, sie stehen für einen verliebten Mann, der zwischen den geöffneten Blüten (sprich Frauen) sinnestrunken

tanzt.

Im Betrachten solcher Schalen erkenne ich wehmütig die ganze Armut unserer ach so modernen Zeit. Einer Zeit, in der solche Gefäße für viele Zeitgenossen nur kitschiger Schnick-Schnack darstellt.

Für den aber, der sie lesen kann, sind sie ein Vermächtnis. Sie sind Mahner und erinnern, dass Sinnlichkeit ein Teil unseres Menschseins ist, und nur dem, der sie pflegt, kommt sie ganz zur

Entfaltung.

This pot is a testimonial from old times. I just call it “Pot of the four Seasons”. The queen of flowers is pictured here, the peony

(Chinese: Mu-tan). It is the flower symbol for spring (first photograph, on the left). Poets have rendered homage to it and its beauty stands for utmost eroticism. On this picture it is not shown

together with other plants. This means that in this case, it stands only for the season of spring. When paired with other plants, the symbolism could be entirely different.

The following plant is the lotus (second photograph, on the left). Lotus is one of the eight buddhist treasures. It stands for summer and its combinations with other

plants have countless meanings. Flowers, buds and seed heads are full of signs and symbols and give the lotus a special, poetic eroticism.

The chrysanthemum (Chinese: Chue, second photograph, on the right) is the flower of autumn, it symbolizes long life. Also here the constellations with other natural

symbols have countless meanings.

The plum (Chinese: Mei, first photograph, on the right) or the plum blossom twig is a botanical symbol for winter. Often, just like on this pot, it is depicted in

combination with bamboo and pine. They are the three stalwarts in the cold season. The plum flower also has erotic meanings in combination with other symbols.

Even the butterflies on each of the pictures have erotic meaning, they represent a man in love dancing sensually between the open flowers (symbolizing

women).

When looking at such pots I wistfully think about the poverty of our modern times, in which containers like these are just kitschy gadgets in the eyes of many

people.

But for those who can read them, they are an artistic legacy. They remind us that sensuality is a part of being human and that only those who nourish it can fully

develop it.

Wunderschöne alte Schale zum Träumen / A beautiful ancient pot, for dreaming

Größe: 30 cm x 20 cm x 10 cm Alter: ca. 100 Jahre

Size: 30 cm x 20 cm x 10 cm Age: about 100 years

Größe: 35 cm x 22 cm x 9 cm Alter: ca. 80 – 100 Jahre

Size: 35 cm x 22 cm x 9 cm Age: 80 – 100 years

Auch die Malerei auf dieser Schale steckt voller Symbole und Bedeutungen. In der deutschen Literatur wird nur mager über solche Bildsymbole berichtet, daher sind nicht alle Darstellungen gut zu übersetzen, und ihre Bedeutungen zu Verstehen und zu entschlüsseln. Aber, ich kann mir gut vorstellen, dass jeder Stein, jeder Baum, Vogel, Ochse, Fischer und Strohhütte eine Bedeutung hat.

The paintings on this pot also are packed with symbols and meanings. In European literature there is not much information about their

symbolism, so it is not easy to interpret all the illustrations and to understand and decrypt their meanings.

But I would imagine that every stone, tree, bird or ox, every fisher and straw hut has a special meaning.

Dargestellt ist hier eine Flusslandschaft im Frühling, die sich sehr harmonisch in

die flache Form der Schale einfügt.

Auf der rechten Seite der Schale wird ein Hirte dargestellt der einen Ochsen an einem Strick zieht (vielleicht auch ein Wasserbüffel, der typisch für Südchina ist). Es kann gut sein, dass dieser

Ausschnitt für eins der sechs Bilder von „Ochs und Hirte“ steht. Sie weisen auf das höchste Ziel des religiösen Lebens hin (siehe ZEN, in Gleichnis und Bild, O.W. Barth Verlag).

Here we see a river landscape in spring, integrated harmoniously with the shallow shape of the pot.

The right side of the pot shows an oxherd pulling his ox on a rope (maybe a water ox, which is typical for south China). It may well be that this detail stands for one of the six “Ox Herding”

pictures. They indicate the highest goal in religious life (see also “A Flower does not talk”, Zenkai Shibayama, Kyoto 1966, “Zen Oxherding Pictures”, Zenkai Shibayama, Kyoto 1967).

___________________________________________________________________________

Die hier im „Schatzkästchen“ vorgestellten Schalen stammen alle aus der Sammlung von Paul

Lesniewicz.

Text und Fotos: Peter Krebs

All pots presented are from the collection of Paul Lesniewicz.

Text and photographs: Peter Krebs

Translation: Heike van Gunst